(I have a guest post up in the form of a video chat over on Just Jane 1813! Be sure to stop by!)

On 27 February 1812 the famous poet Lord Byron gave his first speech in a debate of the House of Lords, and it was a doozy. It caused all sorts of social waves, and was reprinted in several papers. Some loved it, and some hated it, but almost all of Britain heard about it.

Classified as “mad, bad, and dangerous to know” by one of his many lovers, Lady Caroline Lamb, he was as much a devotee to human rights and to easing the suffering of the lower classes as he was to literary arts and the lists of love. Thus, it is fitting that his first speech was during a debate on the Frame Breaking Act, when the Parliament was trying to decide what to do about the Luddites.

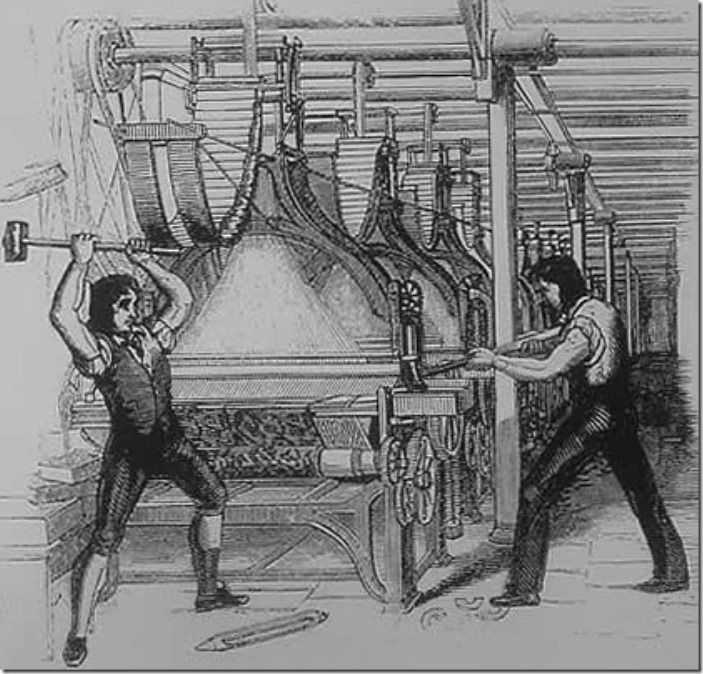

Thanks to anti-Luddite propaganda, the Luddites are remembered as people who were foolishly afraid of technology and against progress. I have even called myself a Luddite, when explaining to someone my ignorance of new technologies. However, the modern usage of the word Luddite is completely wrong. The Luddite riots, which happened off and on from 1811-1816 and then reoccurred in agriculture during the 1830s, were ACTUALLY about socioeconomic substance, inequality, starvation, and unionised labour resistance.

“[T]he Luddites did indeed understand the advantages which mechanization would bring,” Raymond Boudon, a sociologist at Paris-Sorbonne University, wrote in his Analysis of Ideology, citing the work of influential historian Lewis Coser. But “their machine-wrecking was an attempt to show the owners of the new textile mills that they were a force to be reckoned with, that they had a ‘nuisance value’. By acting in this way, their main objective was to gain concessions from the employers.” The Luddites weren’t technophobes, then. They were labor strategists.

One of the reasons Luddites stayed to fight for jobs rather than scarpering away to work in another field was because it was still ridiculously hard to relocate for work in other areas. The Statute of Cambridge in 1388 forbade labourers from leaving their native area “without a testimonial, showing reasonable cause for his departure, to be issued under the authority of the justices of the peace. Any labourer found wandering without such letter, was to be put in the stocks until he found surety to return to the town from which he came.”

Moreover, laws for the next 500 years made moving into a community while poor, or not being able to support yourself and/or your family, was punishable by imprisonment. If you were destitute, it was assumed you were no better than a beggar or vagrant and would be treated as a scourge rather than an work-seeking labourer. You could be brought in to work in places where there was a need for factory hands via special permission, but it just uprooting and heading out to find a job was discouraged.

Meanwhile, people were being driven away from their rural homes en masse by the Enclosure Act of 1801, which allowed land owners to basically fence off at will the lands poorer people were once able to use for pasturage, farming, forage, and other means of subsistence. The displaced had to head for bigger cities, where they were less likely to be punished for their wandering and more likely to find work. Of course, the exploitation of these workers was extreme.

Additionally, workers not from England itself, like the Irish immigrants, were able (via a loophole in the laws) to move to the factory cities much more easily than a former farmer even a few counties away. This enraged the starving poor of rural England, who blamed the ‘shifty Irish’ for this injustice rather than the upper class who had written the laws. The anger at the Irish workers unleashed incandescent anti-immigrant feelings against ‘Paddy’ throughout the country, and fuelled the assertion that the Irish were subhuman mongrels.

Byron was well aware of these facts, and had a great deal of sympathy for the Luddites. He made an impassioned, rational, and fact-based plea to help, rather than harm, the Luddites, and begged his fellow Parliamentarians to put the good of humanity before the benefit of a handful of men.

So, of course, his side lost the vote resoundingly.

Most men of wealth feared nothing on earth so much as workers fighting back or destroying property, and so they instead voted to make frame-breaking a capital crime. Now any labourer who was caught destroying machines (or attempting to destroy machines, or maybe looking like they wanted to destroy machines) would be hanged. If the rabble wanted to fight for their subsistence instead of quietly starving to death so the factory owner could grow richer, then the rabble needed to die.

Instead of passing reforms that would have made life tolerable for the working class and poor, the government doubled-down on harassing them and keeping them in ‘their place’. Upper-class Britain had seen what had happened in France, and the powers-that-be were still smarting over this whole ‘democracy’ nonsense in America, so they thought their best course of action was to incarcerate, export, or legally murder anyone who might be unionising workers or agitating for more voting rights. Because sending out spies within your own citizenry and clamping down even harder on the freedom of speech and the press is a much more rational solution than even the most modest redistribution of wealth.